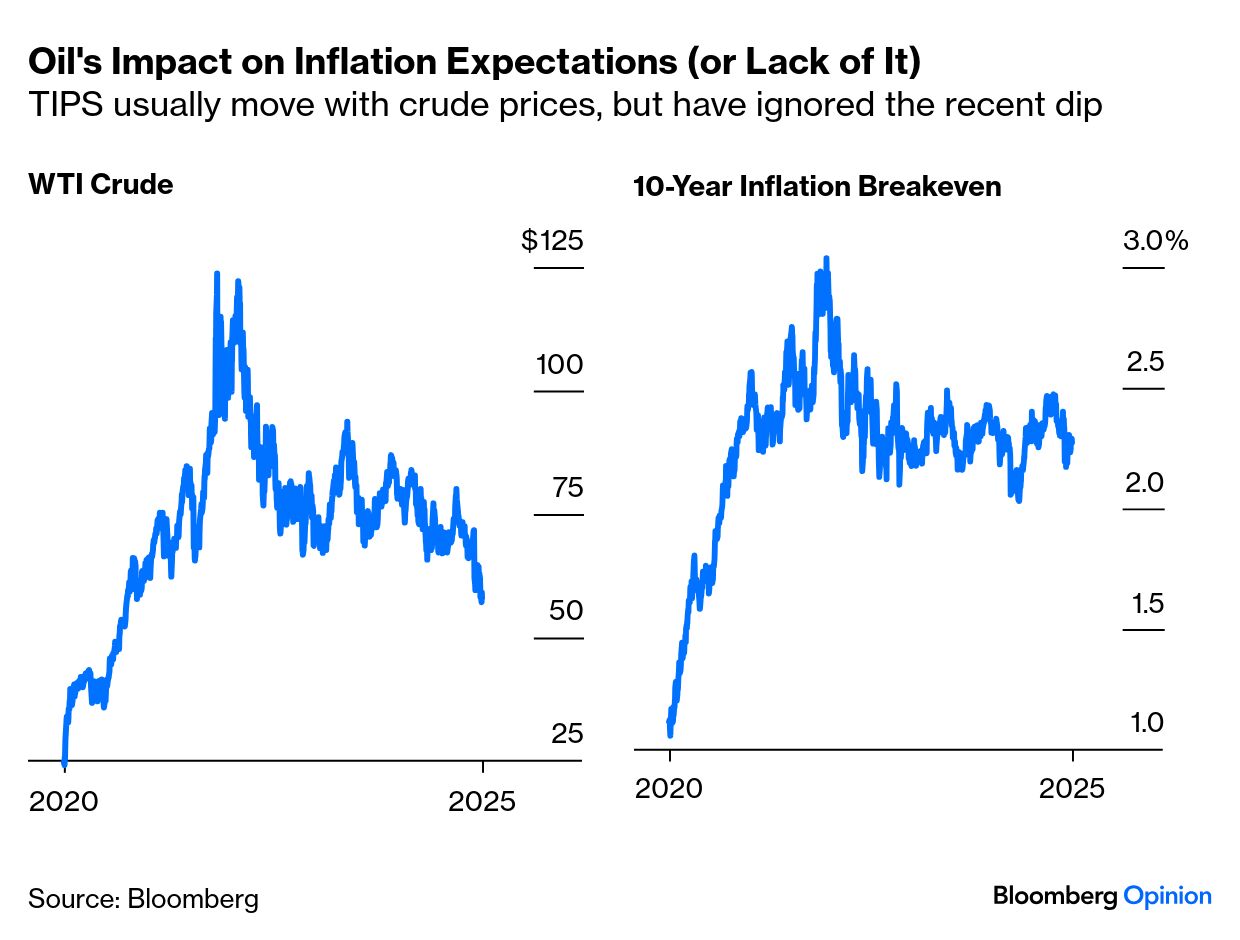

| The Federal Open Market Committee has just pronounced that the risks of stagflation are rising, and nobody much seemed to care. That was because neither the members nor anyone else knows where tariffs will be after July 8, when the current pause is set to expire. Small wonder, then, that equity and bond markets proved far more sensitive to the latest headlines on trade than to the FOMC. The Fed’s precise words were that “the risks of higher unemployment and higher inflation have risen” since it last met. That was before the Liberation Day tariff announcement on April 2 and all the excitement that followed. Few can sensibly disagree with this, or with Chair Jerome Powell’s protestations that everyone would have to “wait and see.” This doesn’t just refer to whatever free trade deals can be hammered out, but to the effect those levies have on behavior in the economy. So far, they’ve prompted purchases to be brought forward, so there is minimal hard data to gauge tariffs’ eventual impact on employment and inflation. Titanic developments, such as a historic appreciation for the Taiwan dollar, demonstrate that all is not well with the tech supply chain and that much remains uncertain: With the Fed predictably on hold, tech mattered more. Breaking news shortly before Wall Street’s close that the Trump administration was planning to lift restrictions on chips used for artificial intelligence had a much bigger impact on stocks than the Fed: Oddly though, the Fed’s perception that risks have risen has had minimal impact on market expectations for future rate changes. Hopes for a cut next month have dwindled, with the odds now put at only 20%. Why would the Fed move before the tariffs pause ends on July 8? But confidence that three cuts are on the way this year remains strong. The market still expects the fed funds rate to be at 3.5% at year-end, substantially unchanged since Liberation Day: The market evidently believes that Powell will wait and see, and also appears to think that tariffs’ ultimate impact will be to limit growth without stoking inflation. Three cuts over the year’s last four meetings would imply a seriously slowing economy. Why the confidence? The single biggest reason comes from the oil price, which has recently collapsed to its lowest since early in 2021. That directly implies downward pressure on inflation, and crude prices usually translate directly into bond market inflation breakevens. That hasn’t happened thus far, with 10-year inflation forecasts barely changed as oil tumbles. (If you’re reading this on the terminal, press the “Open in GP” button so you can see the two series overlaid — normally the relationship is remarkably close):  Cheaper oil isn’t necessarily a total boon. It reduces input prices for industrialists who might be facing a tariff bill for importing components — but it also eats into the incentives for producers to drill, baby, drill. That explains why OPEC+ has been happy to let the price fall, led by Saudi Arabia. It can also be a symptom of falling global demand. Oil took its first dramatic dive on Liberation Day, which was seen to be a hit to global economic strength. Unlike stocks, it hasn’t recovered in the slightest. Another strange phenomenon is that the bear market in crude has had virtually no effect, as yet, on prices at the pump. This is very unusual: If we assume that cheaper crude will, at the end of the long refining process, trickle through to cheaper prices for American motorists, that is reason to hope consumer confidence can be bolstered, and inflation can stay under control. So maybe that justifies the expectations of rate cuts. But a lot more will need to go into that calculation… |