|

Globalization did not hollow out the American middle class

The protectionist narrative is more myth than fact.

|

For years, I’ve been calling for the U.S. to promote manufacturing. When Americans started getting excited about reindustrialization, I cheered. I was a big supporter of Joe Biden’s industrial policy, and I even praised Donald Trump for smashing the pro-free-trade consensus in his first term.

Trump’s tariffs haven’t changed my mind about any of that. Yes, the tariffs are a disaster. But they’re not a disaster because they promote manufacturing; indeed, they are deindustrializing America as we speak, by destroying American manufacturers’ ability to leverage supply chains and export markets. When America has finally realized the futility of Trump’s approach, it will be time to turn once again to the task of reindustrialization — in fact, that task will be even more urgent, given the damage that Trump will have done.

And yet at the same time, I think there’s a misguided narrative about globalization, manufacturing, and the American middle class that has taken hold across much of society. The story goes something like this:

In the 1950s and 1960s, America was a smokestack economy. Unionized factory jobs built a broad-based middle class, and we made everything we needed for ourselves. Then we opened up our country to trade and globalization, and things started going downhill. Wages stagnated due to foreign competition, and good manufacturing jobs were shipped overseas. American cities hollowed out, and we became a nation of winners and losers. The college-educated upper middle class thrived in their professional jobs, while regular Americans were forced to fall back on low-wage service work. Eventually the rage of the dispossessed working class boiled over, resulting in the election of Donald Trump.

You can see this narrative at work in Joe Nocera’s recent much-discussed post in the Free Press:

No one anymore, on the left or the right, denies that globalization has fractured the U.S., both economically and socially. It has hollowed out once-prosperous regions like the furniture-making areas of North Carolina and the auto manufacturing towns of the Midwest. It has been a driver of income inequality…Trump owes much of his political success to the fury that these realities aroused in working-class Americans.

“My dad ran factories in the Detroit supply-chain orbit,” Financial Times columnist Rana Foroohar told me recently. “In the 1990s, the factories started shutting down. And when I would go home in the 2000s, half of my high-school classmates were on opioids.” She added, “The economic theories didn’t connect with the real world.”

Which raises an obvious question: Why did so many economists, policymakers, and journalists like me refuse to acknowledge the problems with neoliberalism for so long? Why were we so quick to label anyone who even flirted with the idea that maybe the U.S. should be protecting its industrial base, just as other countries did, as a Pat Buchanan-like fool?

One big reason was the most basic one: It meant low prices. Companies could keep their costs low by using China’s (and Mexico’s) comparative advantage: cheap labor. At the same time, companies like Walmart and Costco could buy goods directly from Chinese manufacturers, which invariably had lower prices than comparable American goods.

And you can see the narrative at work in a recent series of tweets by Talmon Joseph Smith:

Like all such narratives, this one consists of layers of myth wrapped around a core of truth. But not all grand economic narratives are created equal — in this case, the layers of myth are thick and juicy, while the core of truth is thin and brittle. Everyone knows about the China Shock paper and the collapse of manufacturing employment by about 3 million in the 2000s. That’s the core of the story, and it’s very real. But there are a lot of big important economic facts that place that story in perspective, which most of the people talking about this topic seem not to know.

Ultimately, the trade-driven collapse in manufacturing was only a small part of the economic story of America over the last half century.

America is not actually that globalized

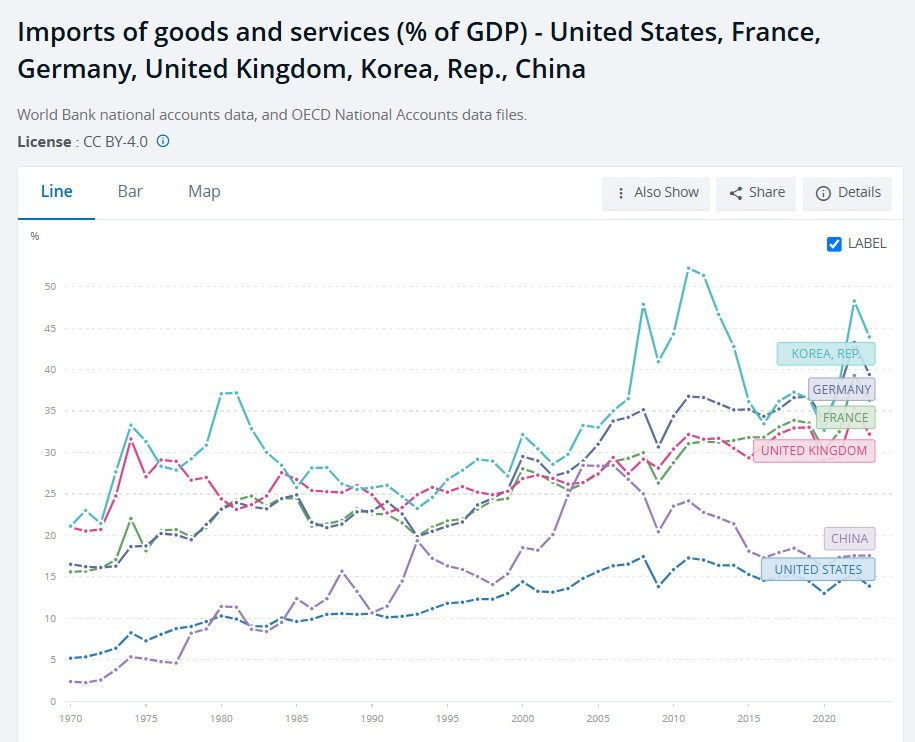

Pundits and politicians alike talk incessantly about the flood of cheap Chinese goods into America. But overall, this is a small percent of what we buy. The U.S. is actually an unusually closed-off economy; as a fraction of GDP, imports are much lower than in most rich countries, and lower even than China:

|

Trade deficits are an even smaller amount of GDP. U.S. imports of manufactured goods minus exports are equal to about 4% of GDP per year. Our trade deficit with China is about 1% of GDP.

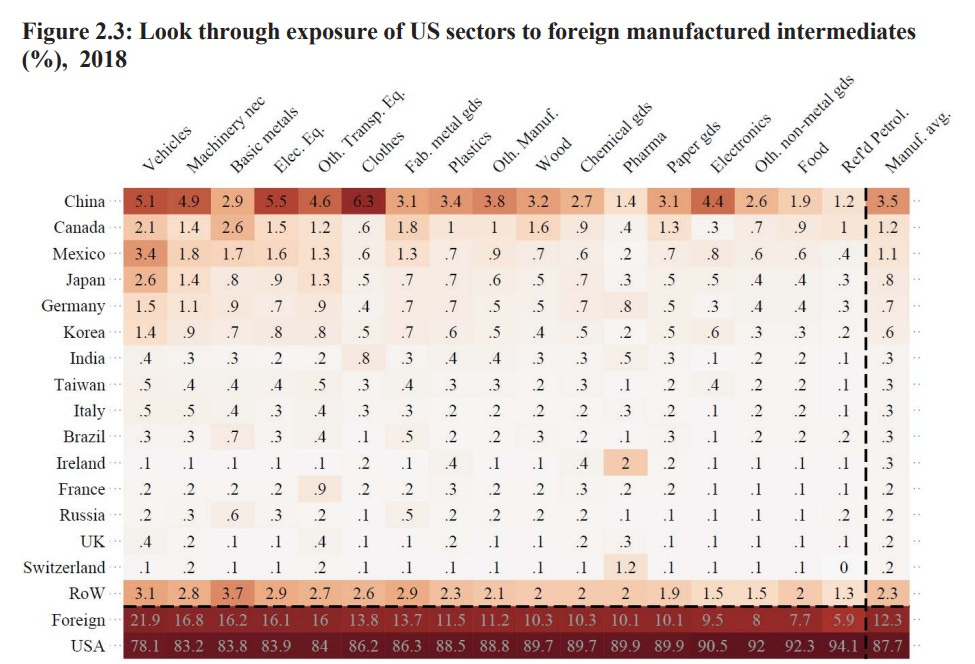

In terms of imported components, America manufactures most of what it uses in production. China’s exports to the U.S. are actually more likely to be intermediate goods rather than the consumer goods we see on the shelves of Wal-Mart — another thing the typical narrative misses. But even so, China makes only about 3.5% of the intermediate goods that American manufacturers need:

|

So if we eliminated trade deficits, would it reindustrialize America? Even assuming that we replaced the imports 1-for-1 with domestically made goods, the impact on manufacturing’s share of U.S. GDP would be fairly modest. Here’s Paul Krugman:

Last year the U.S. ran a manufactures trade deficit of around 4 percent of GDP. Suppose we assume that this deficit subtracted an equal amount from spending on U.S. manufactured goods. In that case what would happen if we somehow eliminated that deficit?